The age-friendly health systems movement1 promotes 4 evidence-based geriatric care principles known as the “4Ms”: What Matters, Medications, Mobility, and Mentation.2 These principles reflect the shift from problem-focused care to acknowledgment of the interaction of factors that contribute to quality of life and health outcomes for older adults. Mental health professionals, including psychiatrists, psychologists, psychiatric nurse practitioners, psychiatric clinical pharmacists, licensed professional counselors, and social workers, play a critical role in treating older adults who would benefit from age-friendly care. Our case example highlights the role of the mental health clinician in implementing each component of the 4Ms.

Case Report

Mr A is an 82-year-old man who presented to a mental health outpatient clinic after his wife expressed concerns about low motivation and activity (which was surprising as Mr A was once very adventurous and piloted small aircraft) as well as disrupted sleep and frequent irritability. Mr A recently enrolled in the Veterans Health Administration due to increasing medical concerns including hypertension, hyperlipidemia, abdominal aortic aneurysm status postendoscopic repair, and benign prostatic hypertrophy. He was also recently diagnosed with subcortical vascular cognitive impairment; imaging revealed extensive nonspecific microvascular white matter disease bilaterally with symmetrical atrophy.

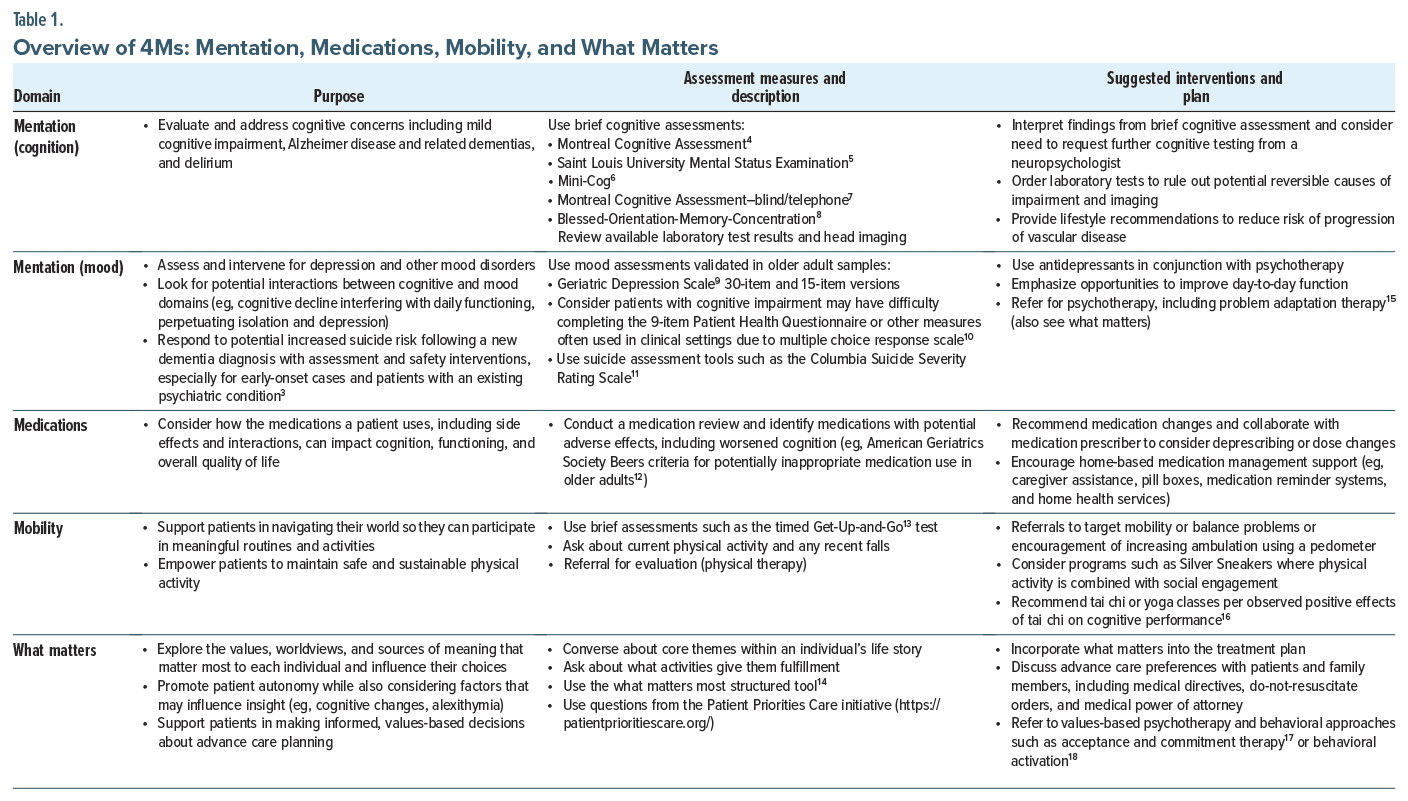

Mentation. Within the domain of mentation, the clinician aims to identify and treat mood-related and cognitive conditions including dementia, depression, and delirium (Table 1). In our case, components existed of both cognitive decline (dementia) associated with vascular changes as well as a mood presentation that can be conceptualized as “vascular depression.”19 Evidence has shown that selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) treatment may be beneficial in delaying progression of cognitive changes for some individuals in addition to addressing mood concerns.20 A low-dose SSRI was well tolerated by Mr A, and he reported a significant improvement in his functioning, including his willingness to go on daily walks.

Mobility. The ability to engage in physical activity via adequate gait and balance while avoiding falls promotes vascular health as well as mood improvements (see Table 1). A multisite study21 of nearly 800 older adults using accelerometry data demonstrated that a 10% increase in physical activity was associated with significantly improved mood symptoms. For Mr A, encouraging physical activity could help manage his subcortical vascular condition.

Medications. The nature of cognitive changes in the context of subcortical ischemic disease includes difficulties with executive function (planning and estimating consequences of actions) and motivation, which can influence medication management and health monitoring (see Table 1). In Mr A’s case, this includes medication management and refills as well as self-monitoring blood glucose and blood pressure. Furthermore, potential adverse effects of medications (both prescribed and over the counter) with older adults should be monitored closely, including medications that may diminish cognitive functioning (see Table 1).12

What Matters. Individuals with vascular-related cognitive decline face barriers in establishing feasible and safe priorities in health care and lifestyle management. Clinicians should identify what matters most to their patients and connect these values to specific and appropriate actions that impact well being (see Table 1). A clinician could discuss values that underly Mr A’s love of aviation (adventure, freedom, and mastery) and identify feasible activities that reflect these qualities (eg, taking a cruise and watching planes come and go at a local airport). Considering patient preferences and values can also lead to discussions around advance care planning.

Conclusion

The age-friendly health systems movement is redesigning health care in all settings—from outpatient to inpatient to long-term services—to proactively care for older adults and align health care service delivery with personal wellness goals and values.2 Thus, it is imperative that mental health clinicians not only incorporate the 4Ms into their care but also consider their role as change agents within their clinics and health care settings in spreading these practices.

Article Information

Published Online: October 3, 2024. https://doi.org/10.4088/PCC.24cr03780

© 2024 Physicians Postgraduate Press, Inc.

Prim Care Companion CNS Disord 2024;26(5):24cr03780

Submitted: May 26, 2024; accepted July 24, 2024.

To Cite: Davis CH, Gould CE, Schultz SK. Age-friendly health systems: the medical and mental health connection. Prim Care Companion CNS Disord. 2024; 26(5):24cr03780.

Author Affiliations: Psychology Service, VA Palo Alto Health Care System, Palo Alto, California (Davis); Geriatric Research Education, and Clinical Center, VA Palo Alto Health Care System, Palo Alto, California (Gould); Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, Stanford University School of Medicine, Palo Alto, California (Gould); VISN 23 Clinical Resource Hub, Veteran Health Administration, Minneapolis, Minnesota (Schultz). Drs Gould and Schultz contributed equally to this work.

Corresponding Author: Carter H. Davis, PhD, Psychology Service, Veterans Affairs Palo Alto Health Care System, 3801 Miranda Ave, Palo Alto, CA 94304 ([email protected]).

Relevant Financial Relationships: None.

Funding/Support: None.

Patient Consent: Oral consent was obtained to publish the case report, and patient information has been de identified to protect anonymity.

Disclaimer: Views expressed in this article are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the Department of Veterans Affairs or the federal government.

ORCID: Carter H. Davis: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-3142-4784

References (21)

- Fulmer T, Mate KS, Berman A. The age-friendly health system imperative. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2018;66(1):22–24. PubMed CrossRef

- Mate K, Fulmer T, Pelton L, et al. Evidence for the 4Ms: interactions and outcomes across the care continuum. J Aging Health. 2021;33(7–8):469–481. PubMed CrossRef

- Alothman D, Card T, Lewis S, et al. Risk of suicide after dementia diagnosis. JAMA Neurol. 2022;79(11):1148–1154. PubMed CrossRef

- Nasreddine ZS, Phillips NA, Bédirian V, et al. The Montreal Cognitive Assessment, MoCA: a brief screening tool for mild cognitive impairment. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53(4):695–699. PubMed CrossRef

- Tariq SH, Tumosa N, Chibnall JT, et al. Comparison of the Saint Louis University Mental Status Examination and the Mini-Mental State Examination for detecting dementia and mild neurocognitive disorder—a pilot study. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2006;14(11):900–910. PubMed CrossRef

- Borson S, Scanlan JM, Chen P, et al. The Mini-Cog as a screen for dementia: validation in a population based sample. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2003;51(10):1451–1454. PubMed CrossRef

- Dawes P, Pye A, Reeves D, et al. Protocol for the development of versions of the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) for people with hearing or vision impairment. BMJ Open. 2019;9(3):e026246. PubMed CrossRef

- Katzman R, Brown T, Fuld P, et al. Validation of a short Orientation-Memory-Concentration Test of cognitive impairment. Am J Psychiatry. 1983;140(6): 734–739. PubMed CrossRef

- Yesavage JA. The use of rating depression series in the elderly. In: Poon LW, Crook T, Davi LK, eds. Hand book for Clinical Memory Assessment of Older Adults. American Psychological Association; 1986:182–191.

- Bamonti PM, Heisel MJ, Topciu RA, et al. Association of alexithymia and depression symptom severity in adults aged 50 years and older. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2010;18(1):51–56. PubMed CrossRef

- Posner K, Brown GK, Stanley B, et al. The Columbia–Suicide Severity Rating Scale: initial validity and internal consistency findings from three multisite studies with adolescents and adults. Am J Psychiatry. 2011;168(12):1266–1277. PubMed CrossRef

- American Geriatrics Society Beers Criteria Update Expert Panel. American Geriatrics Society 2023 updated AGS Beers Criteria® for potentially inappropriate medication use in older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2023;71(7):2052–2081. PubMed

- Podsiadlo D, Richardson S. The timed “Up & Go”: a test of basic functional mobility for frail elderly persons. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1991;39(2):142–148. PubMed CrossRef

- Moye J, Driver JA, Owsiany MT, et al. Assessing what matters most in older adults with multicomplexity. Gerontologist. 2022;62(4):e224–e234. PubMed CrossRef

- Kanellopoulos D, Rosenberg P, Ravdin LD, et al. Depression, cognitive, and functional outcomes of Problem Adaptation Therapy (PATH) in older adults with major depression and mild cognitive deficits. Int Psychogeriatr. 2020;32(4):485–493. PubMed CrossRef

- Yu AP, Chin EC, Yu DJ, et al. Tai Chi versus conventional exercise for improving cognitive function in older adults: a pilot randomized controlled trial. Sci Rep. 2022;12(1):8868. PubMed CrossRef

- Plys E, Jacobs ML, Allen RS, et al. Psychological flexibility in older adulthood: a scoping review. Aging Ment Health. 2023;27(3):453–465. PubMed CrossRef

- Pepin R, Stevens CJ, Choi NG, et al. Modifying behavioral activation to reduce social isolation and loneliness among older adults. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2021;29(8):761–770. PubMed CrossRef

- Taylor WD, Schultz SK, Panaite V, et al. Perspectives on the management of vascular depression. Am J Psychiatry. 2018;175(12):1169–1175. PubMed CrossRef

- Bartels C, Wagner M, Wolfsgruber S, et al; Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative. Impact of SSRI therapy on risk of conversion from mild cognitive impairment to Alzheimer’s dementia in individuals with previous depression. Am J Psychiatry. 2018;175(3):232–241. PubMed CrossRef

- Felez-Nobrega M, Werneck AO, El Fatouhi D, et al. Device-based physical activity and late-life depressive symptoms: an analysis of influential factors using share data. J Affect Disord. 2023;322:267–272. PubMed CrossRef

Please sign in or purchase this PDF for $40.

Save

Cite